The Sobering Story of the Aral Sea

Having researched Uzbekistan for four years prior to my trip, I felt like I had a good idea of what I could expect from my first visit to the famed Silk Road destination. What I couldn’t have foreseen, however, was the stark and lasting feeling to hit me while in the country’s wildest frontier – the Aral Sea.

.jpeg)

Regarded by many as the biggest manmade environmental catastrophe of the 20th century, the Aral Sea was the world’s fourth largest inland water in living memory but has been reduced to less than 10% of its former size. A quick Google search of before and after pictures will leave even the most phlegmatic in sheer disbelief that an entire ‘sea’ could almost disappear in just 50 years. With no viable solutions, the remaining water is set to evaporate in the near future.

.jpeg)

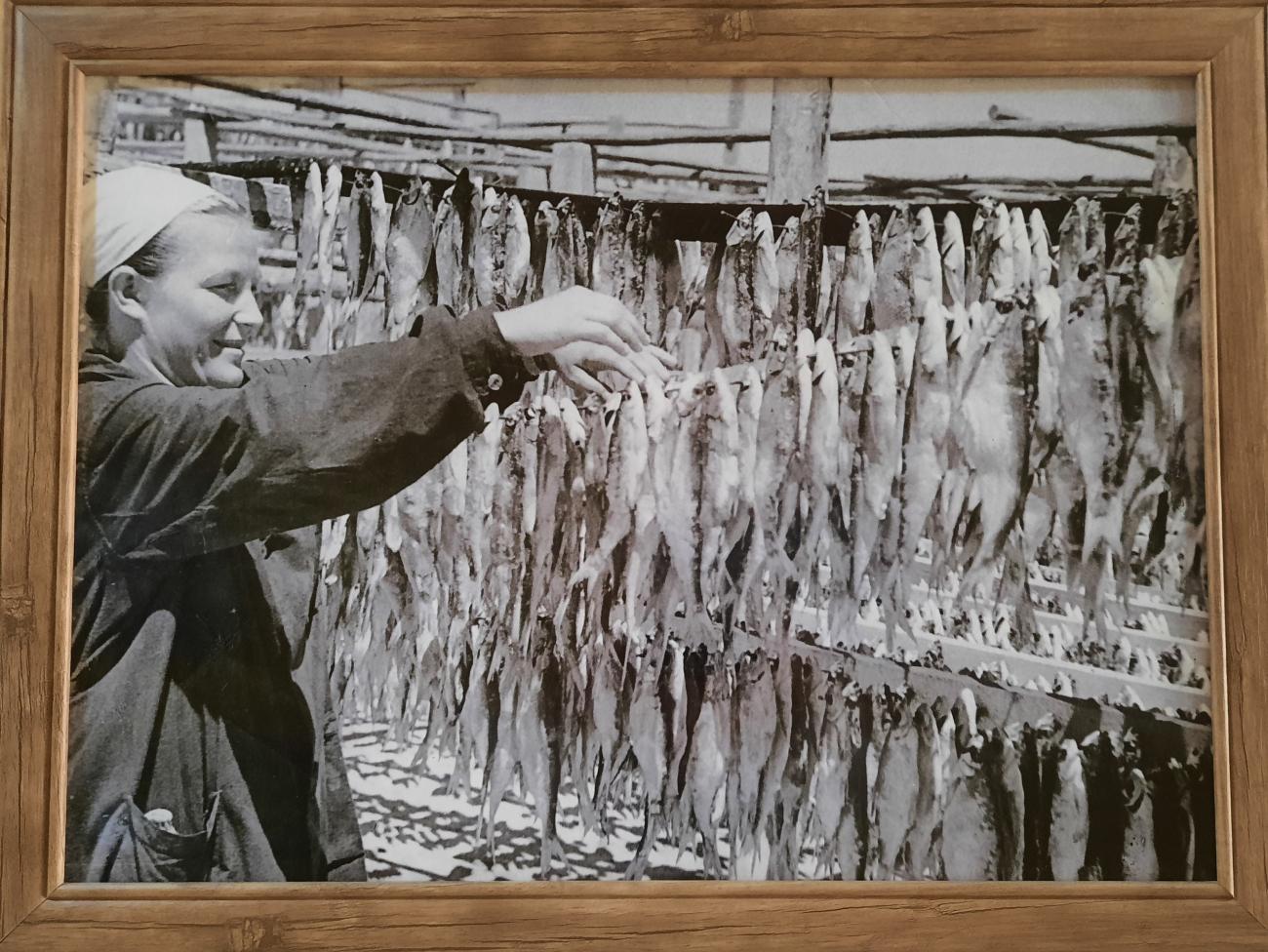

Serious mismanagement of the region’s natural resources has produced chilling consequences, stark evidence - if any was needed - of humans’ ability to cause a calamitous impact on nature. To increase cotton production, the Soviets began a large-scale diversion project in the 1960s, using irrigation channels to divert enormous amounts of water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that fed the Aral Sea. This led to the drastic shrinking of the sea at an alarming rate and, as the lake reduced in size, its salinity became evermore concentrated eventually killing off the fish and with it, the last of the once-thriving fishing industry. As well as loss of water and income, run-off industrial fertilisers and pesticides heavily polluted waterways and seeped into the soil causing serious and long-lasting health problems for the locals, adding to their plight.

.jpeg)

Plans have been thought up over the years to try and remedy the worsening situation but, due to political challenges and the enormous costs involved, none came to fruition. So, where does that leave the region and its people now? Drained, despondent and defensive - rightly so - but also defiant. From the hardy wildlife still roaming the deserted landscapes to the hard-working residents who continue to call the area home, and like the Aral Sea itself, all is not lost yet.

Tourism plays a very small role in the area so some may wonder whether it’s worth a visit - is it just disaster tourism? My trip in early June was a predictably solemn experience. However, submerged within the gravity of the situation, I was surprised to find stubborn glimmers of hope.

.jpeg)

Tours start from the Karakalpakstan capital, the city of Nukus, home to the brilliant Savitsky Museum. From here you’ll set off in 4x4s to the Aral Sea region which can be achieved via a full-day tour to Moynaq, the infamous port town that once sat at the Aral Sea’s shore, or a longer overnight journey towards the northeastern border with Kazakhstan to reach the remaining water that now barely spans the two countries. Given the unforgiving heat of the Uzbek deserts in the summer (43C daily when I was there), my guide suggested that we stop first at the Mizdakhan Necropolis during the cool of the morning – a suggestion I was incredibly grateful for.

A highly recommended visit for anyone in the area (even if not Aral Sea bound), the site spans more than 2,000 years of history and conquest. From the bones found in Zoroastrian ossuaries and the Islamic mausoleums to the graves of current-day Karakalpaks, it’s a fascinating way to understand how beliefs and practices have been shaped over the years through the unusual yet insightful perspective of death. Bidding adieu to the cities, we then set off on a two-and-a-half-hour drive to our next stop.

.jpeg)

Moynaq (also spelt Muynak), the most important fishing town during the area’s heyday, has subtle reminders of its glory days all over town. Having once required a boat to reach it, it now sits more than 150km from the water. As we approached its entry sign brandishing a fish logo it was lunchtime, so our driver pulled up to a house down one of the residential backstreets. Here, the lady of the house prepares homemade lunches and rents out extra rooms to the trickle of tourists that dare to venture this far during Uzbekistan’s travel season (May-October) - her resourceful way of making an income after her husband passed away.

After filling up on hearty plov, we drove to the Museum of Aral Sea History on the edge of town, a humble exhibition providing an introduction to the town’s history during its zenith, and the area’s most photographed site, the ‘ship graveyard’. These 12 rusting hulks, which used to happily float atop lively waters in their prime, now lay on the dried-up lakebed decaying in the desert sun. Painting a somewhat paradoxical picture, from 2018 to 2022, Moynaq was chosen as the location of Uzbekistan’s electronic Stihia Festival as a means of promoting environmental awareness. This saw life pumped back into the otherwise quiet town for one long weekend each year – a seeming contrast of energies that recurred during my visit.

.jpeg)

Passing the abandoned old fish factory as we left town, it was approximately another three hours to reach the water’s edge where the only sign of life is a yurt camp set up by a Kazakh-Karakalpak. This latter half of the journey is a very bumpy one across the former lake floor with 360-degree views extending out to an endless sea of beige desert scattered with shrubs, specks of seashells and salt and the odd gas and oil rig. We made several stops during this time and a sobering tranquillity sunk in deeper at each. Wild winds have spread the toxic sand and salt across the region contaminating more land and water, and so efforts have largely focussed on the more cost-effective planting of saxaul shrub to try and stifle expanding desertification. Perhaps ironically, the lack of light pollution produces a wonderfully dark canvas for the star-spangled night sky, providing some great star gazing in the region.

.jpeg)

A change in landscape comes as you approach the Ustyurt Plateau, the former boundary of the Aral Sea. From a viewpoint on the top of the plateau – a roadless no man’s land where locals dare not drive at night for fear of getting lost – travellers look out across and below to the empty space once filled with rich waters. Having suffered such devasting loss, it was at least reassuring to see that the plateau’s wild charm remained, as its depressions ebbed and flowed into the distance.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

I was also pleased to hear of more sightings of saiga antelope in recent years in the Saigachy Reserve (2016) and the Aralkum National Nature Park (2022) that flank the remaining water, and wondered whether this empty space would teem with life once again. For now, a few roaming camels provided some activity every now and again. Dotted around are also a number of small ‘cemeteries’ belonging to nomadic tribes, recognised by the few tombstones left behind with inscriptions.

.jpeg)

Traversing the dusty, lonesome plateau, the day’s melancholic undertone is then vigorously disturbed by the exciting first glimpses of the blue waters below. Arrival at the lake coincides with the early evening heat beginning to cool and the lull of the waves provides a soothing melody - an ideal setting for the kind of deep reflection demanded when visiting somewhere like the Aral Sea. Despite the dark shadow cast by its disastrous history, a curious beauty continues to glisten over the region. After a scrub back at the camp we sat down to dinner, set up on the edge of the plateau with the sun setting over the lake.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Following a cosy night’s sleep in the yurt, it was time to head across the wild terrain back to civilisation. However, the more adventurous can also extend their time, heading further into the Saigachy Reserve to explore its craggy, rose cliffs known as the Aral Sea Canyons, an area that UNESCO is considering developing as a Global Geopark. It’s also possible to travel to the red sands of the Aralkum where recently spotted herds of saiga are thought to have been kept isolated on the heavily guarded Vozrozhdeniya Island (Resurrection Island), the location of the notorious Soviet-era Aralsk Bioweapons lab. A shorter detour can also take you to Barsakelmes, a major salt pan reminiscent of the Uyuni salt flats in Bolivia.

.jpeg)

The road leading to and from the camp is particularly rugged, but a pleasant surprise lurks within these uneven mounds as tortoises pop up out of small holes in the ground between April and May every year for the nesting season. Twenty minutes from the camp is also the site of a ruined caravanserai, once an important stop along the ancient caravan trade routes, where a small part of the wall and a solitary view of the Aral Sea remain intact.

A slightly different return route brings us to the lesser known but somewhat happier Sudochye Lake (also spelt Sudochie), which still receives a sprinkling of water from the Amu Darya. Protected by reeds, it is thankfully still home to a variety of waterbirds and has piqued the interest of birders with flocks of flamingos, pelicans and swans amongst those that still paddle in its waters.

Designated an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA), it functions as a stop along a migratory corridor for birds heading to Siberia in the spring and flying back south in the autumn. However other birds, such as an eagle that briefly came to check on us, can be spotted at other times. The lake is overlooked by an ancient tower, once also used as a lighthouse for ships crossing the lakes, and Urga Village, a since abandoned fishing village where gulag prisoners were exiled. All that remains are some building foundations and a few wooden crosses known as the ‘orthodox cemetery’. From here it takes around six hours to arrive back to Nukus - plenty of time to ponder timely questions about our relationship with nature.

.jpeg)

Often described as a toxic wasteland, I had a pretty bleak picture of today’s Aral Sea before arriving. I left, however, with a sense of gratitude – grateful to have seen its unexpected appeal, to have been reminded of the delicacy yet resilience of nature, and to have hopefully been a part of the early days of a brighter future for the region. Though the smattering of tourism might not generate huge cash flows today, it may just play a role in bringing some awareness and helping to turn the tide in the future.

.jpeg)