Salaam Baalak - A Salute to Delhi’s Street Children

Salaam Baalak literally translates to ‘Salutes a Child’, the name and mantra of a non-profit trust in India’s capital that has been supporting street children of the city for over 35 years.

During a recent visit to Delhi, I was privileged to visit and spend time with the team at the Salaam Baalak Trust (SBT).

I was there to hear more about the trust’s city walks programme, which trains young adults, who have been in its care, as tour guides. The tours offer visitors the chance to not only see some of the city sites, but gain a real insight into street life in Delhi from the perspective of their guides.

I learned so much more.

Meeting me on arrival was guide Ajay and his beaming smile.

‘Delhi is the best city. In 10 years, it has given me so much’, he says.

He loves the vibrancy, the history, the arts scene, the markets and the people, and is knowledgeable about the city he now calls home. His enthusiasm is infectious.

Ajay was first supported by the SBT as a 12-year-old runaway. Now 22, he talked me through the operations of the charitable organisation as we strolled through the busy lanes around the New Delhi Railway Station.

The station is the second busiest in the country (Kolkata tops that list), with 16 platforms and hundreds of trains a day arriving, departing and passing through the station. As we look up at the information board, there are literally trains coming and going every few minutes.

It’s here, next to one of the station's chaotic entrances, that the SBT opened its first centre.

The railway station is a hot spot for street children to congregate, often for safety in numbers. It’s also the goal of many runaways from other areas of the country to make it to New Delhi Station.

Ajay told me that the station was one of the areas he found refuge when he was living on Delhi’s streets and that the trains were good pickings for food and ‘work’.

He said he would eat food that rail passengers had left behind and would collect all of the empty plastic bottles to sell at the recycling market opposite the station.

‘I could earn anything from 100 rupees to 1000 rupees (£1 - £10) a day’.

‘You had to spend anything you earned the same day, otherwise others may take it from you.’

‘What do you think I spent my money on?’ Ajay asked.

‘Jalebi and Bollywood movies!’ he laughed.

Jalebi is a sticky sweet treat made by deep-frying batter and soaking it in sugary syrup. As we walked through the recycling market on our way to try some jalebi, we passed by an elderly lady and her husband who lived in the market and made small clay tealight candle holders to sell. The husband was busy softening the clay with his bare feet preparing it for the next batch of candle holders, while she was giving a teenager a good ticking off.

Ajay said the lady had been in that same spot for as long as he could remember, and all of the kids called her mother.

Ajay’s story

Ajay is a positive light in what is a story of real resilience and determination.

Ajay left his home in Nepal when he was just 12 after conflict within his family. When he refused to continue to work in the fields, he was told to leave and not to return.

‘I had a piggy bank, just like that one’, he pointed to a stall that was selling a variety of clay goods as we continued through the markets.

He had been saving money, which he tells me he earned through gambling. He smashed the piggy bank, took his savings and left.

Ajay had his sights set on Delhi with the hope, like many others, of finding a better life.

Although ID wasn’t needed, afraid of crossing the border alone and being picked up by officials, he said he had the idea to walk close to any random person, so that he looked like their son.

Once across the border, he used India’s rail network to make his way to Delhi.

‘I met a person on the train who said they would help me, but I got lost when we got off at the Delhi railway station and I didn’t see them again.’

He was sitting in a corner in the station when two social workers from the SBT found him.

He was accommodated and looked after at one of the shelter homes, but found the daily routine too structured, and came up with a plan. Himself and many of the boys in his shelter attended a nearby school. One day, when being walked back from school, six of them scattered and ran in different directions.

Ajay spent almost 3-years fending for himself, sleeping rough, gathering food from trains and collecting rubbish for recycling, before returning to the safety and support of the SBT at age 15.

Pointing up at the entrance of the SBT day care centre, he told me he used to jump across from building to building to sleep on the roof.

‘It was safe up there’.

Coming full circle, he goes back to Nepal regularly to visit his family, whom he now gets along well with.

Original Premises by the New Delhi Station

The day care centre by the station and above the police station was SBT’s original premises and is still the first point of call for the trust’s outreach workers who identify vulnerable children within the station area.

Not all of Delhi’s street children are runaways. The circumstances are wide and varied. While many do runaway to escape conflict or abuse, others find themselves in the situation due to trafficking, many also live on the streets with their families, often having travelled to the city to seek work, and some children are simply lost after being separated from their parents on busy station platforms.

Ajay said children getting lost in the chaos of India’s railway stations is common.

The SBT has outreach workers at the station every day, and within the day care centre there is a counsellor, a teacher, two social workers, a part-time psychologist and part-time medic.

The centre also works for drop ins and around 20 – 25 children visit each day, many of whom live on the street with their families and use it as a safe space after school instead of being alone while their parents are still working.

While we were there, a new boy arrived. He was 16 and had made his way to Delhi on his own from Bihar, a state southeast of Delhi bordering Nepal.

‘The first priority is to try and reunite children with their families’, Ajay explained.

Attempting to condense the detailed process into a brief paragraph, new arrivals are assessed by a children’s welfare team and receive medical checks. If contact can be made with the parents, counselling between the child and the parents is arranged. Roughly 75% of children supported return home and follow up checks are made on the child and their welfare. Ajay said roughly 10% run away again.

Inspiration behind the charity

The inspiration behind the Salaam Baalak Trust was the award-winning film Salaam Bombay! directed by Mira Nair, a fictional film that chronicled the lives of street children in Bombay’s slums. During the filming Nair worked with many street children.

In a book that celebrates the journey of the trust, co-founding trustee Praveen Nair said she wasn’t aware of the plight of street children before her daughter made the film.

The lead in the film, Shafiq Syed, received an award for best child actor.

‘That started me thinking that given an opportunity these kids are as good as anyone else. And with that Sanjoy (fellow founder Sanjoy K Roy) and I began’, the book reads.

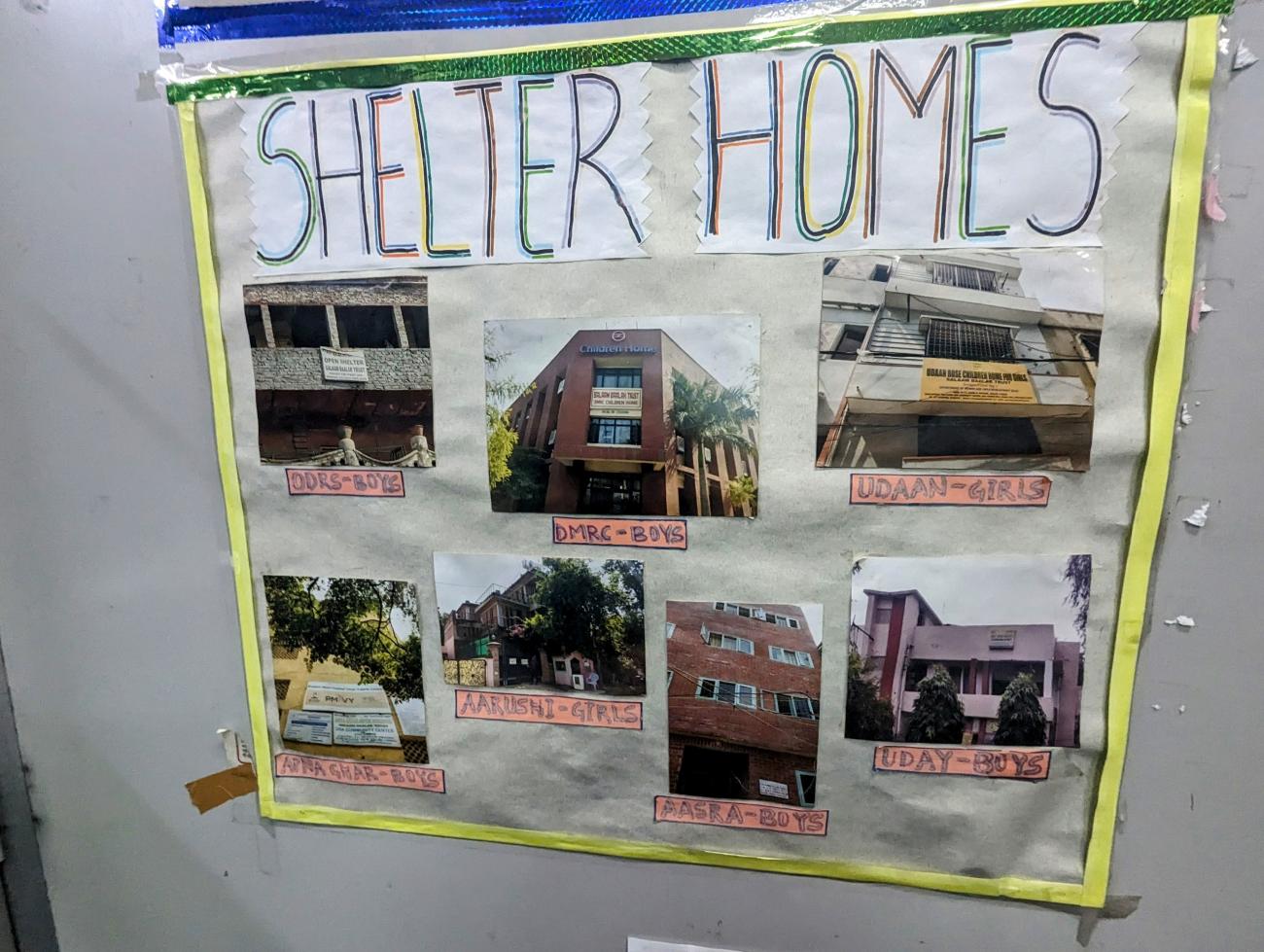

From its humble beginnings in 1988 with three staff supporting 25 children, the SBT now employs 300 staff who annually support over 10,000 children through various outreach, counselling and education programmes, medical support, accommodation with seven shelter homes (two for girls and five for boys) accommodating 600, nine touch points around the city and an emergency child line.

Going back to its roots, the SBT focuses many of its programmes on the arts, giving children the opportunity to express themselves and grow in confidence, including a much-anticipated annual play that is attended by Bollywood actors, government officials, donors and sponsors.

Ajay is actively involved in the arts scene and tells me he played the lead role of Romeo in the last play.

‘When you are on the streets no one listens to your voice, but on the stage, everyone is there to listen’.

Certainly, the quote of the day from this remarkable young man, who along with guiding the SBT city walks, is qualifying as a certified Incredible India Tourism guide. With a Bachelor of Arts degree in Hindi Literature, he has also been attending film-makers workshops and has an ambition to become a Bollywood actor.

The SBT has supported him financially to help him realise his dreams. As they have with Kajal, also a city walk guide, who was placed in the care of the trust at six-years-old after her parents became ill. She has just completed her course to become a flight attendant, and at 21 is excited to soon take to the skies and travel the world.

More than 100 young people have been tour guides through the programme to date.

Wild Frontiers supports the Salaam Baalak Trust by offering the city walk tours as a unique community experience on our tailor-made holidays to India.

India Tours | Undiscovered Rajasthan | Wild Frontiers (wildfrontierstravel.com)

- The hero image on this blog was taken from the book celebrating 35 years of the Salaam Baalak Trust